Over the last few years capabilities of large language models (LLM) increased constantly, and their application ranges steadily broadened. This versatility was achieved by finetuning large foundation models to specific tasks (e.g. instruction following) or domains (e.g. legal texts). These models exhibit excellent performance in producing structured outputs such as code, JSON or SQL. The focus of this article is a business example using Text-to-SQL.

In modern organizations vast amounts of business and proprietary data are stored in relational databases whose efficient access often requires trained staff and good understanding of data structure and data management principles. Many colleagues who need to work with this data lack sufficient SQL skills, making efficient data use more difficult. A typical business world scenario based on information from relational databases may look like this: A marketing department of company needs product A sales figures from last year for all branches in Hamburg and Berlin.

Here is the point where Text-to-SQL systems help bridge the gap between queries phrased in natural language and the extraction of information from relational databases. The quality that LLMs currently achieve makes SQL generation a reliable process. (see, for example reference [1] as a timely review). In business contexts as described above, we therefore see a high relevance for Text-to-SQL systems, which on the one hand combine a user-friendly interface with natural language capabilities and at the same time enable access to a wide range of existing databases, including data warehouses or data marts.

In this blog post, we summarize our findings during the development and testing of a standard Text-to-SQL use case employing a sales database. We will describe the building blocks that make up the complete system, dive deeper into corresponding prompt engineering and outline a typical conversational flow. It turned out that using a capable LLM in the user application for SQL-generation allowed for interaction with the database at various levels:

L0: The immediate level. The user prompt refers to questions concerning the database schema or raw content. Example: "Show me the current database schema" or "Return all values of the column 'brand'".

L1: The query level: This is the conversational level which is most important for the use case where concrete information retrieval tasks based on the schema are issued. Example: "Show me all product names in the 'cosmetics' category customers from 'Hamburg' bought last month". By combining the information from the database schema with the query terms, the LLM is able to generate the corresponding SQL statement, which a orchestrator subsequently forwards to the query engine. In the resulting query string in our product A example the tables/columns 'customer', 'category', 'product.name', 'customer.address', 'sales.date' will be addressed together with required joins and quantifiers.

L2: The referential level: A key advantage of conversational memory lies in its ability to let users reference previous queries easily, eliminating the need to reenter the entire query when only slight adjustments are made. Let’s get back to the example above: The same information with respect to category and time frame is needed, but for the Berlin branch: Entering “Repeat the last query for our Berlin branch” will do the job. Depending on the length of the conversation window and the complexity of the queries a chat with the database at the SQL level is possible.

L2-type communication also happens as soon as the user issues feedback to steer or to correct generated SQL. By considering various database dialects, the LLM can well adapt to the specifics of a database system but still could make mistakes in its generation process. Once a problem is detected by strict syntax and format checking a correction prompt can be provided and enriched by a linter output: "In your last query there is the following problem: <linter output>. Try to correct it". This approach worked well in the rare cases where syntax or formatting issues occurred. In a production setting, users should not be exposed to SQL correction playback. During development, however, a careful analysis of linter outputs helped to shape the system prompt, the schema linking strategy and postprocessing steps. Greater emphasis will be placed on the latter factors when it comes to more advanced database schemas or highly complex queries.

To summarize, by using capable LLMs in SQL-driven business cases, information becomes easily accessible through a text-to-SQL system and will therefore lead to efficient generation of insight, higher data autonomy and resource optimization.

Our goal is to demonstrate how a robust and extensible text-to-SQL workflow can be set up starting from a user query, SQL generation and verification until delivery of the corresponding database results. In actual customer use cases we normally have the following constraints:

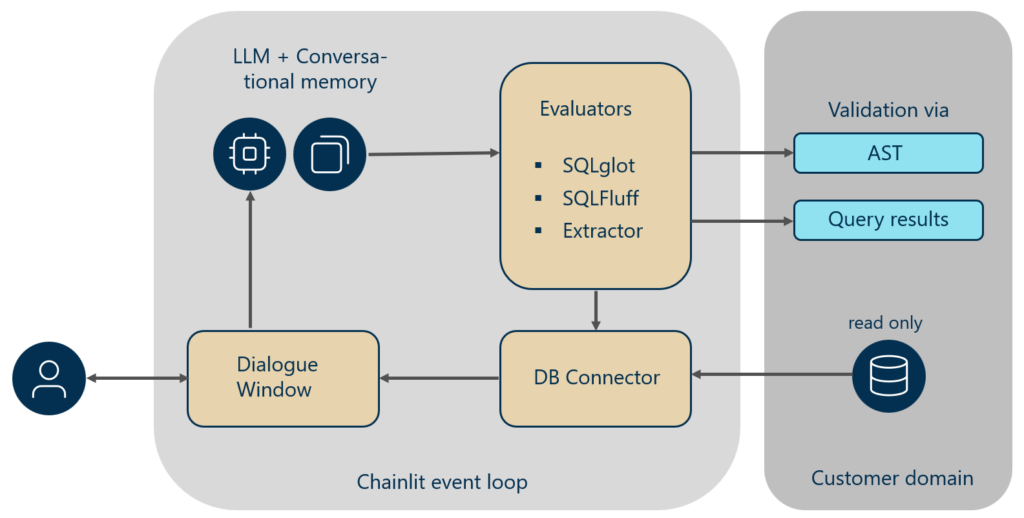

The figure below outlines the workflow.

End-to-end workflow from natural language query to validated SQL execution

The user on the left side in the figure above constantly interacts with the system through a dialogue window where prompts are entered and results are played back. The conversational memory tracks user prompts and generated SQL such that a L2-level conversation is enabled. In each query the LLM receives the system prompt together with the conversation taken place so far. Specific information such as database schema, database type and SQL dialect are inserted into the system prompt on system startup. In our implementation validation messages from the syntax checkers and linters are played back as well for control and debugging purposes. Once the SQL has passed all checks the AST and the retrieved data are stored to allow for additional verification with a customer gold standard. After longer conversations it is recommendable to clear the conversation memory to avoid any bias that may have built up in a chain of queries. Since context lengths are limited, we maintain a conversation memory window of length 20. For our business case demonstration the following components were used:

As mentioned above, finetuning a model is out of scope for getting into production quickly and due to the capabilities of the current LLMs one can steer the model by thoughtful prompt engineering following a few core principles relevant in the context of SQL generation by LLMs. As mentioned in [1] prompt engineering can be divided into three stages, namely preprocessing, inference and postprocessing. When it comes to the construction of our system prompt for high SQL quality we largely adhere to these principles albeit some aspects described in [1] do not apply for our production case. We briefly sketch our construction principles for the LLM system prompt.

Example of LLM-generated structured output for SQL generation

As stated above, level 0 refers to queries that directly relate to the database structure or raw table content and are sometimes needed to reveal specific details on the database:

Example of a level-0 interaction retrieving database schema information via natural language

By maintaining the conversation history, a short follow up question is possible and will automatically generate the extended query internally (the output order of the tuples is arbitrary):

Follow-up schema request using conversational context in a Text-to-SQL workflow

As an example for a real query, we want to find customers who made a purchase in a specific store and within a certain time period.

Example of a level-1 interaction translating a business question into SQL

Now we want to issue a follow-up query by finding the customers now in Hamburg and assuming that the LLM can deduce the missing information from the conversation memory:

Context-based follow-up query resulting in a semantic SQL error

Interestingly, an error in the produced query (despite its syntactical correctness) was observed which is a result of the assumption that the ‘Store’ table has the column ‘City’ which is actually not the case. Here we have a competition of LLMs (high likelihood) internal knowledge that ‘Hamburg’ is a city which overrides the information in the schema that no ‘City’ column exists for the ‘Store’ table. From a database perspective it seems a bit inconsistent to store datapoints related to ‘Hamburg’ in the table ‘Store.State’ but strictly speaking, ‘Hamburg’ is a city-state in Germany which may justify this choice.

Having localized the problem, we can straightforwardly produce results by explicitly tell that 'Hamburg' is a store state in a L2-type conversation (observe the occurrence of German-sounding customer names in the database results, indicating the correctness of the data):

Correcting a context-based query using conversational feedback

In summary, the examples shown are not very complex but demonstrate that natural language interaction with a SQL database can be realized without serious impediments in short time. Internally, we also conducted successful benchmarks including more complex queries where, for example, nested SELECTs were generated from a more elaborate natural language request.

Looking ahead, we plan to

Our text-to-SQL example project demonstrates that natural language querying can be made practical and reliable when combined with sound engineering principles. It bridges the gap between human intent and structured data, enabling organizations to unlock the full value of their databases through conversational interfaces.

[1] L. Shi et al., A Survey on Employing Large Language Models for Text-to-SQL Tasks, arXiv:2407.15186 (2025).

[2] B. Ascoli et al., ETM: Modern Insights into Perspective on Text-to-SQL Evaluation in the Age of Large Language Models, arXiv:2407.07313 (2025).

[3] X. Wang et al., Self-Consistency Improves Chain of Thought Reasoning in Language Models, arXiv:2203.11171 (2022).